In 1963, the American philosopher Wilfrid Sellars, in an article entitled ‘Philosophy and the Scientific Image of Man’ proposed a distinction that, although it has played very little part in the major history of twentieth-century philosophy, seems to become ever more pertinent.

Sellars distinguishes between the ‘Manifest Image’ and the ‘Scientific Image’. That is to say, he remarks a growing divergence between the account of the world delivered by the sciences, and the image of the world that we customarily conduct our lives according to—our image of ourselves as self-willed, autonomous agents in a world that is full of meaning. Sellars inquires into how these images conflict, and asks whether philosophy can somehow bridge this gap, or resolve this disparity, and if so, then how.

Now, of course, Sellars is not the only philosopher to have written about this gap between the two images of the world: in fact, much of Western philosophy in the twentieth Century has concerned itself, often with a certain creeping horror, with the growing gap between the way in which human beings recognise themselves, others, and the world around them, and a vision of the world—rationalised, mechanised, or materialist—that the sciences have progressively opened up. At least since Nietzsche, philosophers have diagnosed this new image of the world as the germ of nihilism, the disrupting of human meaning and the beginning of the quest of an ungrounded and disoriented man to restore meaning to the world somehow.

Needless to say, the disparity between the manifest and scientific images becomes all the more disturbing when we begin to think about ourselves—when we contemplate the fact that there is nothing special or central about the world we live in—Copernicus—that we are animals, descended from the contingent evolutionary processes–Darwin—and that perhaps our conviction and trust in our own thoughts is misplaced–Freud, and latterly, neuroscience and cognitive science.

Sellars however does not seek to prioritise the manifest human image as if it were an originary, authentic truth which the scientific image damages. He is sceptical about the idea that there is somehow a spontaneous, truthful image of ourselves that should be preserved.

I introduce the term ‘spontaneity’ here because I think it’s another very useful term. The notion of ‘spontaneity’ was developed furthest by French Epistemology in the twentieth century, following Bachelard. What was at issue here, before Sellars, was the way in which scientific thought seemed to make a decisive break with our intuitive image of the world. The way things appeared to us spontaneously was not the way things were revealed to be by rational scientific thought. And through the 60s and 70s this idea of spontaneity saw an interesting convergence with the Marxist critique of ideology, a critique that sought to reveal our most fundamental presuppositions and models of the world, our spontaneous framework for understanding, as ultimately determined by socio-political structures that were non-personal, that couldn’t be understood in terms of individual human agents. Now, in this case, our spontaneous image of the world is, as Althusser said in his pithy way, ‘spontaneous, because it is not’—the spontaneous appearance of ideology owes, precisely to the fact that in fact it is manufactured elsewhere, in a place and by mechanisms that, in principle, we don’t have access to.

What’s interesting in Sellars is that his way of being evenhanded with the scientific and manifest image is precisely to take this approach—to treat the manifest image as a complex theoretical construction, just as much as the scientific image is. He tries to withdraw from the manifest image its apparently immediate and spontaneous nature, and to show that it, too, is something constructed, on the basis of our biology, our social patterns, and our language. It’s like a sort of ‘black box’—in the same way that a camera seems to produce an image in a very simple and straightforward way, but in fact is a complex piece of machinery, a kind of construction of congealed theory; our minds also produce the spontaneous or manifest image through a series of complex mediations.

This doesn’t resolve the question of how to reconcile the manifest and scientific image, but it goes some way towards posing the question in a more tractable way.

Now, in philosophy, very broadly speaking, one could point to two veins of thinking that respond to the manifest and the sceintific image: phenomenology has sought to ‘bracket out’ the scientific image of the world, seeing it as a theoretical imposition that cannot be taken for granted. Phenomenologists try to capture the experience of being in the world and to understand how our understanding of the world is always mediated through our place in it and the way we try to make meaning of it. Science, for them, is just one of the ways in which we do so. On the other hand, philosophers of science have tried to resolve our natural way of seeing the world, our natural language and our meaning-making, into phenomena that are explicable in materialist terms.

In contemporary philsophy I think we find two positions that speak directly to the problem of the two images. On one hand, we have the ‘democracy of objects’ espoused by Bruno Latour and what has become known as object-oriented philosophy. Here one tries to maintain the even hand of Sellars, and allow that the objects of the manifest image—the things that seem naturally to appear to us as objects and phenomena, and our construction of meaning around them—are, really, objects, on the same plane as the objects that science describes to us. And what philosophy should do is to try to describe the way these different types of objects interact. Here, science becomes, not a direct and objective description of the world, but one human practice among others, one way of constructing objects. The problem I see with this approach is that one loses both the truth-claims of science, and one loses the critique of ideology—on this level playing field, one becomes unable to make any distinction between the ways in which objects are produced, and hence ultimately while trying to save it, one loses any orientation towards a reality that could said to be real apart from human thought. In the absence of a critique of ideology or spontaneity, also, one becomes dependent on a framework of thought that is purely philosophical, and this brings with it the danger that this framework is unconsciously influenced by the objective appearance of things at a particular historical time: thus, the philosophies of Graham Harman and Tristan Garcia have a disquieting affinity to a world in which everything is exchangeable, packaged up into commodified objects, and flattened onto one plane, like a sort of Google-philosophy.

On the other hand, one has what is called eliminative materalism—that is, the position that says that we need to progressively disenchant ourselves of our spontaneous or manifest image, by recoding this image in the terms that science delivers to us. We have to learn, ultimately, to speak and to live our lives in the real, inhuman world that we have discovered, and bit by bit let go of the manifest image. This is a quite startling proposal, a sort of cultural revolution, really. NO-one has yet made any proposals for how this might be done, and this is something I find very interesting: What is the difference between thinking this, and culturally putting it into action? I’ll come back to this. But let me just remark on some shortcomings of this position too. The problem is that, in ‘eliminating’ the objects of the manifest image, one often deprives oneself of any means to talk about them. I once had a philosophy lecturer who invented a term for this type of thought: ‘nothing buttery’—when one presents to this type of philosopher an object of interest, perhaps something drawn from the manifest image, something meaningful and important, they simply reply…it’s ‘nothing but’ evolution, ‘nothing but’ physics, and so on. So I think this way of thinking risks depriving us of the ability to think about certain things. Secondly, and on the contrary to the democratic or object-oriented approach, it can often rely on a rather hard-and-fast idea of science, and ignore the tentative nature of scientist’s hypotheses, the very real political and social dimensions of science.

There is a political dimension here that is very important. It relates to the nature of ideology today. As follows: if we don’t attempt rigorously to think this gap between the manifest and scientific image, we can be very sure that marketing and advertising are quite capable of mobilising both of them in order to sell us products, and ultimately to sell us an image of ourselves that we consume. Newspapers are filled with incoherent amalgam of ‘nothing buttery’—stories about great scientific breakthroughs—and appeals to spontaneity. Advertising sells us an image of ourselves as powerful, spontaneous, empowered individuals at the same time as telling us that such-and-such a chemical, enzyme, or vitamin has been scientifically proven to provide this spiritual power-up. Exactly as in the famous ad, what reigns supreme today is an inconsistent ideological mixture of ‘the science bit’ and ‘because you’re worth it’. I think this space is where a lot of Pamela’s work sites itself.

So, what about skin? I think skin could be a very acute point at which we could interrogate these two images. Not only because we understand more and more about what skin is, and perhaps will be able to generate it in a synthetic manner, and this synthetic skin is a kind of at once fascinating and repulsive symbol of the disconnect between the two images.

More fundamentally because skin is such an important symbol for who we are and how we interact with others, it is so saturated with meaning, that it is difficult for us to think about it in any other way. Why is there skin? The very question introduces a bizarre alienation in regard to something that is so intimate and significant to us.

Merleau-Ponty, the great phenomenologist, who once evoked this strangeness in referring to skin as ‘the sack in which i am enclosed’, was one of the philosophers who have attempted to reconcile the two images. In (very) brief, what he suggested was that, whilst we can’t demote the scientific image in favour of the phenomenological image of reality, what we have to do is to make far more effort to understand that the way in which we know the world, the way in which phenomena are constructed. He suggested that there was a third series of objects which were not accountable through a naturalistic, scientific explanation, but nor were they spontaneously-delivered products of the human’s image of the world. It is here, he suggested, that culture takes place.

What I would suggest is that, in order to overcome the duality of the image, we would need to interrogate culture both through a critical lens and a scientific optic. It may be true that the way in which we see the world is fundamentally the product of what we could call ‘the spontaneous ideology of the organism’. As the vulgarised newspaper science stories tell us, one thing after another that we hold dear has been shown ‘in the lab’ to be nothing but an evolutionary trait, nothing but the effect of chemicals in the brain, and so on. At the same time, we should acknowledge, as Sellars did, that there is not just one fixed manifest image, it is changing all the time and being ‘contaminated’ by the scientific image. So, for instance, when I say, ‘that really gave me an adrenaline rush’, or ‘the endorphins really started to kick in when I went swimming this morning’, I am beginning, perhaps, to understand myself in a different way.

I’d like to refer in general to Pamela’s work, and what skin becomes. There is no skin-as-biological-material in Pamela’s work, what appears in her work is skin as a sort of aesthetic material, a symbolic stock. This is the same way in which it is used in visual culture, a kind of powerful but abstract trigger that hooks right into our spontaneous impulses and powers of recognition and self-recognition. At the same time, however, by presenting skin directly in this peculiar way, she makes us recognise it as such, and we begin to wonder, what relation does this abstract skin-stuff have to the biological thing that we know skin is? In other words, the work, in-between ‘the science bit’ and ‘I’m worth it’, tends to dramatise the divergence between the manifest and scientific images, opening up the space of culture in which the two are mobilised by culture and ideology, but in which, also, we might be able to challenge them by conjoining the scientific image, and a critical reflection on the manifest image, to form some ideas that somehow encompass this complex object.

The immediate response here is that of a human presence, and mark making, and of bodily substance. But there’s something strange: If the paint was red rather than skin-colour it would make sense, a kind of desperate act of mark-making in blood. But there is the strange displacement at work: here, skin itself is understood as an act of meaning-making: what we tend to do is to place, onto the world, skin as a sort of emblem or brand.

But here, the symbol that seems both full and transparent, both meaningful and immediately related to ourselves, just appears as an opaque material.

Here the substance is a material used in movie prosthetics, which comes in many different skin tones, symbolic at once of the power of the symbol of skin color and the notion of infinite diversity under capitalism, reflected in the plastic water bottle. Here, again, in a strange displacement, we see skin as a symbolic ‘stuff’ inside a second skin, that of the commodity; suggesting that the ‘sack in which I am enclosed’, with its reassuring notions of enclosure, limitedness and individuality, also has some relation to the shopping bag and the act of identifying with consumer products.

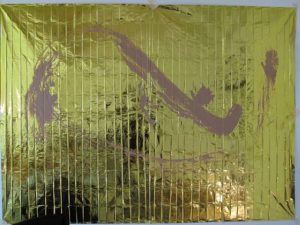

Finally, here the skin has been reduced to its function of protection: it is that which keeps ‘us’ in, but it is also, ultimately, a biologically functional membrane that keeps the sensitive inner body shielded from the outside. Perhaps, far from being the most sensitive and alive part of us, instead, as in Freud’s theory of trauma, it is the part of us that had to die and become hard to protect us from the environment. Its purpose is not to reflect meaning, but to reflect harmful radiation, wind and rain.

I would suggest that ‘skin’ is the name for a complex type of object that is not captured either by a democracy of objects or by an eliminativism. It’s an object that is a kind of mysterious ‘X’ that exists at the juncture of many different disciplines of knowledge and production, and that we don’t yet know. We would be able to realise this if only we were able to step out, for a moment, from our spontaneous assumption that it is the thing we know best of all. I think Pamela’s work helps us do this. In a kind of deliberate obstruction of visual culture, which is based both in our manifest image and in capitalism’s manipulation of it, what seemed to be the most transparent, radiant thing of all, a perfect symbolic mirror in which we reflected ourselves, turns out to be mediated, thinglike and opaque.