If there be ‘true’ londoners, they are to be pitied

Born into its cradle, the city a true home,

a negligible backdrop, a place of comfort;

Those who feel equal to its sophistication.

Only those from outside discover the real London

(‘Real’ not ‘true’—a distinction that must be upheld:

A never-complete becoming, irrational number

As opposed to a supposedly-known entity).

We do not presume to say those who are born and bred

cannot attain this state; only that they also

must cultivate alienation, throw aside

the blanket of homeliness they cast over the city.

Must accept they too share the utter dislocation

Of which London is the perpetual cinema.

Equally, the outsider, drawn ineluctably

into the phantom web of workaday normality

must free himself, by gargantuan efforts of will;

Wrest himself loose, flee back into vagabondage

Only the immigrant is wide-eyed and anxious

enough to imbibe this raw chaos a little.

Like the smog that catches in his throat, first of all

an assault, then a queasy symbiosis in which

he begins to exude London and then London

begins to penetrate into his darkest dreams

Black and white: Bill Brandt’s study in monochrome.

Francis Bacon under the gaslamp, Hampstead Heath.

The heath jumpcuts abruptly to african scrub

and blurred animal forms heaving in the heat.

Burrowing below-ground where light makes shadows flesh,

staggering out of the Colony Room smog,

veering like a breached longship. Vagabond navigation,

reading the signals through vapour of dipso nights.

A world through the champagne glass, through the lugubrious

camera lens of Deakin AKA Conlin, the

notorious dwarflike lowlife photographer2

An emigré, self-described slum boy from Liverpool

He gropes, one-eyed, semi-conscious behind the lens

toward the heart of this infernal machine.

The stranger’s first glimpse of london is most likely

to appal 3

And Thomas de Quincey, Mancunian exile

—all of Wales could not contain his wandering—

walked, a solitary and contemplative man through

London: Oxford Street, stony-hearted stepmother!

Thou that listenest to the sighs of orphans and drinkest

the tears of children.4

—He paced the terraces,

scouring the valleys north to Marylebone.

And Arthur Conan Doyle, an Edinburghian

come via Vienna, dissected eyes with Freud;

Dickens, Portsmouth to Chatham, to Marshalsea prison;

From Birmingham Sax Rohmer, Limehouse Exoticist.

Its greatest luminaries are those who came from without;

Its proper essence fiction, miscegenation.

The reality of the fictional London

overflows the truth on every side.

When the Elephant Man appeared as if from nowhere

in a shop premises in the Whitechapel Road

towards the end of November 1884,

he was in his early days as a professional freak.5

David Lynch’s movie The Elephant Man draws

on an already-potent fictional tradition:

I understood a certain English thing, you know, but

for the film I got inspiration or ideas

more from books of London than from London itself…6

And an inheritance: Brit Celluloid BC

(Before Colour: before its mendacious promise

of a kaleidoscopic future beyond the

seedy decline of british society).

Ealing noir, day-for-night east-end police chases

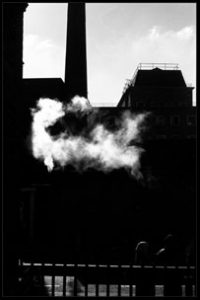

issuing in endgames played out across the steam-shrouded

tracks of railway sidings. Oppressive and gloomy.

And David Lean’s Dickens flicks: These were no ‘adaptations’:

The marshes were just a long black horizontal

line then; as I stopped to look after him; and the

river was just another horizontal line;

and the sky was just a row of long angry red lines….7

Dickens in monochrome; writing like a camera

(Eisenstein discovered a ‘lap dissolve’ in the text).

Blood and Soot for Magwitch, gibbets under red clouds;

Ash and lace, Miss Havisham: White veil…dress…shoes…hair of white…8

The essential is that London is black and white:

an energy-processing monster that incites

its elements to extreme lambency and then

discards them as light-absorbent, burnt-out crusts.

I was walking around a derelict hospital

and suddenly a little wind-like thing came and

entered me, and I was in that time – not only

in that time in the room – but I knew that time.

I knew what it was like then, and it came out of that hospital.

Architecture is a recording instrument.

I’m sure that’s right. And that’s what happened. It was just

unraveling and I was picking it up.9

The Old Royal London Hospital, Whitechapel Road,

A time-tunnel into apocryphal London,

brings the unhuman breath of Lynch’s inspiration

full-circle.

Synonymy of human body and industry….Darkness.

Boiled and bleached bones. White clouds rising from below.

Steam and Scalpel.

The hospital museum houses a replica

of Merrick’s sackcloth hood. The stitches bring to mind

that slow, deliberate zoom into the single square eyehole,

into the nightmares of the Elephant Man:

Filled with puffing steam-monsters, dark smoggy streets, and

the curse of monstrosity and the lash of cruelty.

No more compelling exhibit than the building:

Merrick is only a monstrous sign, avatar

of a psychogeographical papilloma.

This perplexing structure, haphazardly extended

to house medical technologies that always

stayed one step ahead, new pathologies

of the industrial revolution.

Treves bowed over the prone figure of a man

on an operating table: we’re seeing more and more

of these machine accidents nowadays.10

Or you see pictures of explosions –

big explosions – they always reminded me of these

papillomatous growths on John Merrick’s body.

They were like slow explosions. And they started

erupting from the bone… what got me going was

the idea of these smokestacks and soot and industry

next to this flesh.11

Steam is the element of Merrick’s kindly soul:

his birth is announced with the slowmotion billow

of a puff of steam. Recaptured, abandoned,

his return journey is heralded by white clouds;

The train, the steamship, and then again the steam train,

ending at Liverpool Street. White ineffable clouds.

But in his dreams he wanders cities of blackness,

dirty streets populated by jeering children,

factories with rows of men chained to great machines

in which they are pistons. Despondent resonance

of Dickens’ Coketown, distilled essence of the industrial city,

where the piston of the steam-engine

worked monotonously up and down

like the head of an elephant

in a state of melancholy madness.12

With the opening shots, visual reconstruction

of the showman’s florid etiology of

Merrick’s condition, we already understand

a strange transmutation of image into flesh ;

knocked down in the street by elephants, the frightful

image of the creatures on the retina of

Merrick’s mother as she faints passes directly

into the womb, imposing its form upon the

budding embryo.

According to the logic of the film, which is

the logic of this city, at the limit,

images impregnate, mutate what is inside.

Everywhere, relics of paradigms overthrown.

Discarded piles of 50s minicomputer

tangled with pieces of iron bedstead.

The arteries of long-obsolesced fuel supplies,

studded with taps and switches and cast-metal outlets,

still cling to the walls like dead vines. In many places

they simply lock the ghosts in, doors never opened

again save by wrecking-ball.

The saturation of history not yet wrung out

And each time the sensation passes through another

agent it thickens, and reaches consistency,

fiction and environment a sensory emulsion.

Perpendicular surfaces intercutting;

Every wall is an encrypted photogram.

This piece of celluloid adds yet another one.

A membrane inserted between place and consciousness.

Photography is a mediumistic practice

not a self-expression, it dowses for sensations

in their raw state: neither fiction nor document.

The camera unearths sensory proclivities,

your own hidden, subterranean connections;

Continuity with this dense, indifferent,

impossible fabric. The city in reality

is a surface which is all exterior.

No dwelling within it, no breaking the surface

(so that photographs recollect more accurately

than memory itself): Thus there is no comfort

but this abrasive immanence upon which one

grazes and is grazed, injured, disclosed to oneself.

A thousand walks made alone in which I often thought my

pleasure in this ‘exterior’ could never mean anything

except how I was failing in certain ‘interiors.’13

But why berate the surface for its lack of depth,

when we could equally accuse our depths of lacking surface?14

Being young, our souls lack the fibre of this dense

irrational number, which, though one cannot encompass

its impossible totality, cradles us:

no matter which figure we elect as focus

we feel its whole, incomprehensible extension.

London is an atmosphere, a state of being.15

A participation in other people’s fictions.

A self-fulfilling prophecy its authors cannot halt.

Submission to the real; brute point of concentration

Until the journey outward, until we reach places

where one can no longer say the name ‘London’,

though its taste remains, bitter on the lips.

And the last tube station, the workers filing out;

their grey-eyed sagging march a salutary reminder.

Those for whom London is just an odious chore—

do they know it steals their energy to make dreams?

And then finally out. That tremendous relief.

Like a decompression. Life seems lighter. Greener.

You’re elsewhere now. Relaxed. Your thoughts turn to London.

- Norman Collins, London Belongs to Me

- Iain Sinclair

- John Deakin (Essay by Robin Muir in John Deakin: Photographs)

- Thomas de Quincey (Confessions of an English Opium Eater)

- [5]Howell and Ford, True History of the Elephant Man

- David Lynch, Lynch on Lynch

- Dickens, Great Expectations

- David Lean, Great Expectations

- Lynch

- Lynch’s Elephant Man

- Lynch

- Dickens, Hard Times

- Patrick Mullins (personal correspondence

- Deleuze, Logic of Sense (paraphrase)

- Deakin